Q: I have been having problems with low back pain caused by my sacroiliac joint (SI joint) going out of alignment. It seems like something I'm doing in my yoga practice is making it worse. I’m looking for both techniques to snap the sacrum and pelvis back into place and alignment, and advice on how to prevent this from happening. I would appreciate any help with this. I want to keep practicing!

A: I asked Baxter to answer this question because he’s the back care expert (and MD), but since I’ve had this problem myself, I know a little something about it. And maybe even have slightly different advice than Baxter. So Baxter asked me to preface his answer with my own.

First of all, this is a common injury for dancers and yoga practitioners, though not for the general population. In general, forward bends and twists take the sacroiliac (SI) joints out of alignment. Janu Sirsasana seems particularly bad. Backbends can put the joints back into proper alignment. So for now, I'll just suggest that at the end of a practice that includes forward bends and twists (even standing versions of these) that you include some kind of supported backbend before Savasana. Stay in the pose for at least three minutes. You want to restore the curve in your lower back. For example, Bridge pose with a block under the sacrum or even Legs Up the Wall pose with a bolster, where your lower back is arched over the bolster, can help restore the curve. (I’m recommending supported backbends because active backbends—which Baxter recommends below—at the end of a forward bend practice reverse the quieting effect of the practice. This is not really an issue for twisting practices. Regardless, you might try both as everyone is different.)

I also recommend that you read articles on the topic by Roger Cole on the Yoga Journal web site (see Protect the Sacroiliac Joints and Practice Tips for the SI Joints). I’ve learned a lot from him over the years, and have taken his workshop on the SI joint.

Finally, as wonderful as yoga is, it isn't necessarily the answer to everything, so you may need to take time off from certain poses or your asana practice entirely to heal before resuming practice. I, myself, as well as other yoga friends, have had good results from going to a chiropractor who realigns the sacrum manually. My chiropractor is also a yoga teacher—that's the perfect combination if you can find one.

Now for Baxter’s reply.

—Nina

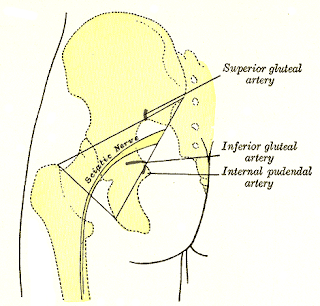

A: It might be helpful to our readers to define what we mean by “sacroiliac dysfunction.” Typically, the joint between your sacrum bone and the two halves of the pelvic bones meet at the right and left side of the posterior pelvic area and form a fairly firm, barely moveable joint called the sacro-iliac joint, or SI joint for short.

The only exception to the “barely moveable” concept is for women about to give birth. In order for the safe delivery of the baby’s head and body, the joints of the pelvis, including the pubic symphysis in front, have to be able to move. The pregnant woman’s body produces a hormone, relaxin, which allows the ligaments around the joints to loosen and permit more movement than normal. Once the baby is safely delivered and breast feeding is concluded, the production and release of relaxin slows and disappears and the SI joint regains its previous firmness.

As Nina pointed out, seems there are a few groups of folks more likely to loosen one side of the joint. These include gymnasts, dancers and yoga practitioners. And indeed forward folds combined with twists seem to be regular culprits. These poses create a torquing action through the pelvis that can overstretch the ligaments and result in more mobility on one side. It is unusual, in my experience, to have someone with both SI joints hypermobile, but I have seen it at least once before.

And indeed, Roger Cole has written some very good articles on this topic, and leads workshops on the topic around the country, which I have attended and can highly recommend. In addition, Judith Lasater has an article in the Yoga Journal archives on her bout with SI joint dysfunction, how yoga brought it on, and how yoga helped her heal it (see Out of Joint). She also has some discussion in her book, “Yoga Body” on the particulars as well, if you want to dive a little deeper. After reviewing the chapter in her book on the pelvis, I found a 1991 review of all the research to that date on intra-pelvic joint movement, including SI joint movement. It seems there is some evidence for minor but distinct amounts of normal healthy movement at the SI joints, but a decent amount of confusion still existed at the time of that study.

As for asana recommendations, I like active backbends, especially Locust, but doing a variation Roger Cole teaches where you have the legs parallel, you strap the ankles and push out against the strap as you lift the legs up. He also recommends doing some asymmetric propping with sandbags, but I have found the symmetric version effective for some students. And I’d put a block between the knees for active bridge and also consider strapping the thighs without a block and push out against the strap as you go up. I believe the theory is that you are creating some lateral space so that the SI joint that is misaligned can pop/slide back into place. These are only two of a whole slew of pose variations that Roger shares in his workshops, so look for the chance to study with him down the road.

And don’t discount the benefit of working with a good physical therapist, as I have had students who were taught some effective simple adjustments they could do to get the SI back in good alignment. And as Nina has mentioned, I have had some students work with chiropractors and osteopathic physicians who got adjustments that resulted in SI re-alignment. Ideally, you would not need to do this very frequently.

This is certainly a hot topic, so keep your eyes and ears open for new developments on the issue of SI joint dysfunction. Thanks for your question!

—Baxter