by Baxter and Nina

Happy New Year, everyone! We've been talking for some time about providing you with a few relaxation tracks that you can stream from our site or download onto your own audio devices. Now, at last, thanks to help from Margy Cohea and Quinn Gibson, we're pleased to release our first two tracks, both featuring Baxter Bell.

We're starting out by providing two shorter relaxation sessions, around 15 minutes each, because we know so many of you have busy schedules or aren't quite ready to commit to a whole hour of yoga nidra. You can play these tracks directly from our blog, or, if you wish to download a track, you can go to our new—gotta love it—Band Camp site (see http://yogaforhealthyaging.bandcamp.com/). Band Camp earns money through the donations you make when you download a track, so if you can afford it, help us support this wonderful site.

The first track is a physical relaxation practice, intended to be practiced in Corpse pose (Savasana). Baxter will gradually guide you, step by step, into a deep relaxation of your entire body and nervous system.

The second track is Baxter's 15 minute version of a yoga nidra practice, which is also intended to be practiced in Corpse pose (Savasana). Baxter will guide you into the state of conscious relaxation that is also referred to as "yogic sleep."

Let us know what you think! And if you have ideas for other audio tracks you'd like us to provide, be sure to let us know.

Friday, December 30, 2011

Thursday, December 22, 2011

Friday Q&A: Ujjayi Breath

Q: You have written quite a bit about breath, which is both interesting and helpful. I am wondering about ujaya breath (sp?), which I learned about from my first yoga teacher (Kripalu). We used to do this when holding more difficult poses, but I am not sure of why this breath is seen as important, and would like to know more about it.

A: Ujjayi (ooh-JAI-yee), known as the “victory” breath, is a breathing technique in which you slightly constrict the opening of your throat to create a slight resistance for your breath. As you inhale and exhale, this resistance produces a slight, raspy sound, which is compared to the sound of the ocean and/or Darth Vader. It is considered to be a heating or energizing breath.

In the Iyengar school of yoga (which is the style that, I, Nina practice and teach), yoga poses are always done with a natural breath, and ujjayi, like any other form of pranayama (breath practices) is only practiced formally in either a seated or reclined position. However, in some other styles of yoga, including Ashtanga Vinyasa Yoga, Power Yoga and Flow Yoga, ujjayi breathing is used continuously throughout the practice of physical postures. This theory behind this is that this particular form of breathing enables you to maintain a rhythm to your practice, take in enough oxygen, and build energy to maintain practice, while clearing toxins from your body. This breath is considered to be especially important during transition into and out of poses, as it helps you to stay present, self-aware and grounded in the practice. This is how Erich Schiffmann puts it:

“The main idea is to coordinate your movements with your breathing. This brings a graceful and sensuous quality to your practice and turns each yoga session into a fluid and creative meditation. As you become skillful at this, the breath and movement will no longer feel distinct. You will experience them as one action, inseparably entwined. You will instinctively breathe as you move or stretch, and move or stretch as you breathe.”

Ujjayi is also taught as part of certain practices by Krishnamacharya and his son Desikachar (Viniyoga), as well as the Kripalu school (and possibly some schools I may have overlooked). Whether or not this breathing technique is “important” depends on the particular school of yoga (or teacher) you follow. And, frankly, because all the styles of yoga that we practice in the U.S. were developed quite recently (the 20th century), I’d say it’s up to you to decide whether or not you want to incorporate ujjayi into your own asana practice. Does it enhance your practice? Or is it a distraction? (Remember, you can always do it on its own, in a seated or reclined position.)

—Nina (with help from Baxter)

A: From a western physiologic perspective, ujjayi creates a resistance to breathing, making breathing a bit more effort-full than it would be normally. In the world of medicine, respirators in the intensive care unit are sometimes set to something called PEEP, short for positive end expiratory pressure, which helps to keep the lungs from collapsing on themselves. Ujjayi may have a similar physiologic effect on healthy lungs. Whether this is of benefit may need further study. I believe the first mention of ujjayi breath comes in the Hatha Yoga Pradipika, Chapter 2, verses 51-53. The author claims it destroys defects in the nadis (energy channels), cures dropsy and disorders of the humours!

—Baxter

A: Ujjayi (ooh-JAI-yee), known as the “victory” breath, is a breathing technique in which you slightly constrict the opening of your throat to create a slight resistance for your breath. As you inhale and exhale, this resistance produces a slight, raspy sound, which is compared to the sound of the ocean and/or Darth Vader. It is considered to be a heating or energizing breath.

In the Iyengar school of yoga (which is the style that, I, Nina practice and teach), yoga poses are always done with a natural breath, and ujjayi, like any other form of pranayama (breath practices) is only practiced formally in either a seated or reclined position. However, in some other styles of yoga, including Ashtanga Vinyasa Yoga, Power Yoga and Flow Yoga, ujjayi breathing is used continuously throughout the practice of physical postures. This theory behind this is that this particular form of breathing enables you to maintain a rhythm to your practice, take in enough oxygen, and build energy to maintain practice, while clearing toxins from your body. This breath is considered to be especially important during transition into and out of poses, as it helps you to stay present, self-aware and grounded in the practice. This is how Erich Schiffmann puts it:

“The main idea is to coordinate your movements with your breathing. This brings a graceful and sensuous quality to your practice and turns each yoga session into a fluid and creative meditation. As you become skillful at this, the breath and movement will no longer feel distinct. You will experience them as one action, inseparably entwined. You will instinctively breathe as you move or stretch, and move or stretch as you breathe.”

Ujjayi is also taught as part of certain practices by Krishnamacharya and his son Desikachar (Viniyoga), as well as the Kripalu school (and possibly some schools I may have overlooked). Whether or not this breathing technique is “important” depends on the particular school of yoga (or teacher) you follow. And, frankly, because all the styles of yoga that we practice in the U.S. were developed quite recently (the 20th century), I’d say it’s up to you to decide whether or not you want to incorporate ujjayi into your own asana practice. Does it enhance your practice? Or is it a distraction? (Remember, you can always do it on its own, in a seated or reclined position.)

—Nina (with help from Baxter)

A: From a western physiologic perspective, ujjayi creates a resistance to breathing, making breathing a bit more effort-full than it would be normally. In the world of medicine, respirators in the intensive care unit are sometimes set to something called PEEP, short for positive end expiratory pressure, which helps to keep the lungs from collapsing on themselves. Ujjayi may have a similar physiologic effect on healthy lungs. Whether this is of benefit may need further study. I believe the first mention of ujjayi breath comes in the Hatha Yoga Pradipika, Chapter 2, verses 51-53. The author claims it destroys defects in the nadis (energy channels), cures dropsy and disorders of the humours!

—Baxter

Pet More Downward-Facing Dogs: Yoga Resolutions for the New Year

by Nina

"Hear now the wisdom of Yoga, path of the Eternal and freedom from bondage.

No step is lost on this path, and no dangers are found. And even a little progress is freedom from fear." —The Bhagavad Gita

When my son was in the fourth grade, he came to me with a problem. His teacher had asked him to write a list of ten possible resolutions he could make for the new year, and the thought of coming up with ten things he needed to change about himself was making him utterly miserable. But to this dedicated student, skipping the assignment was not an option. “What can I do, Mom?” he asked me sadly. “Well,” I replied, “how about if you came up with some resolutions that would be very easy and fun to keep?” “Like what?” He looked at me doubtfully. “Let’s see,” I mused, “how about something like: pet more dogs?”

He lit up with a smile and then went off in much better spirits to write a list of resolutions for his teacher (and keeping the “pet more dogs” resolution throughout the year did turn out to be a lot of fun.) I’m bringing this up now, because if you are planning on making any New Year’s resolutions regarding yoga this year, I’d advise you to take the same lighthearted approach.

If you want to start a home practice, rather than deciding to do full-length class everyday—a rather overwhelming commitment—think small. As my son did, try to come up with a resolution that will be easy to keep and fun to do. How about:

Readers, I’d love to hear about any yoga resolutions that you’re making for yourself or that you’d recommend for others, especially some simple and/or colorful ones.

"Hear now the wisdom of Yoga, path of the Eternal and freedom from bondage.

No step is lost on this path, and no dangers are found. And even a little progress is freedom from fear." —The Bhagavad Gita

When my son was in the fourth grade, he came to me with a problem. His teacher had asked him to write a list of ten possible resolutions he could make for the new year, and the thought of coming up with ten things he needed to change about himself was making him utterly miserable. But to this dedicated student, skipping the assignment was not an option. “What can I do, Mom?” he asked me sadly. “Well,” I replied, “how about if you came up with some resolutions that would be very easy and fun to keep?” “Like what?” He looked at me doubtfully. “Let’s see,” I mused, “how about something like: pet more dogs?”

|

| Back in the Day: My Brother Danny and Our Dog Nikki |

If you want to start a home practice, rather than deciding to do full-length class everyday—a rather overwhelming commitment—think small. As my son did, try to come up with a resolution that will be easy to keep and fun to do. How about:

- Do one Downward-Facing Dog pose a day five days in a row for one week. (You can pet yourself afterward.)

- Look through a yoga book and find a picture of a pose you’ve never done and just try it. (Be sure to laugh if you get totally confused or fall out of the pose.)

- Download a yoga nidra practice or guided relaxation onto your iPod and try it once. (You might become addicted.)

- Clear some wall space, figure out what to use for props, and set yourself up for Legs Up the Wall pose at home. (If you decide to do again some day, you’ll be ready.)

- Practice seated meditation for five minutes a few times in a week. (If it feels good, try it for a second week, then a third, then....)

- Buy yourself an eye pillow and “test” it at once or twice in Corpse pose (Savasana).

Readers, I’d love to hear about any yoga resolutions that you’re making for yourself or that you’d recommend for others, especially some simple and/or colorful ones.

Wednesday, December 21, 2011

Thoughts on Dhyana: Meditation over the Holidays

by Baxter

As I pass through yet another solstice and the modern winter holiday celebrations, I appreciate my own meditation practice, however sporadic it is at times. So I thought today would be a good day to begin introducing the topic of meditation on this blog.

Even trying to introduce the topic of meditation is a bit daunting, however, because there are many eastern traditions that have varied and unique approaches and emphases when they define meditation. So let’s narrow the scope and look at hatha yoga or even classical yoga, where we first find Patanjali in the Yoga Sutras placing dhyana or meditation within the context of the eight limbs of yoga, or the Ashtanga Yoga.

In this model, meditation is considered the second of two stages, beginning with dharana, or one-pointed concentration, and then moving onto dhyana, or continuous concentration or focus on an object. An analogy that Mr. Iyengar and others have used to explain this goes like this: If the mind were a water faucet and the object of my meditation was the bucket below it, when I first begin to focus, the water comes out in drops and moves towards the bucket, but with breaks in between, which represent distraction of the mind from the object. If my practice gets stronger and steadier, a time arrives when my focus is unbroken, represented as a continuous stream of water flowing toward the bucket. This is the stage of “meditation” or dhyana. I am still aware of “me” as the faucet, and the thing I am observing, the bucket, as separate from me, but I am really starting to understand what “bucket” is on a deep level.

There still exists a subject-object relationship. However, in the process of developing this strong, unbroken focus, the normal everyday mental activity almost completely subsides, leading to a more peaceful yet fully present mind state that yogis felt truly beneficial. Modern PET scan studies of the minds of experienced meditators show dramatic quieting of certain areas of the brain and other brain wave patterns emerging that are often related to the state of consciousness seen just before sleep, as well as patterns seen in creative states of mind observed in artists and musicians.

For us, the process begins on a more practical note, when in our first yoga asana practices we are encouraged to simply follow the flow of the breath with our minds to the exclusion of other possible things to focus on. This is essentially the first stage described above: dharana. Anyone who has tried this, if they are really honest, will admit how hard it is to stay on track. One of my teachers used to say that if you could follow the breath for three full cycles of in and out without another distracting thought breaking your concentration, you would reach enlightenment immediately—his way of saying that this is really hard to do, even though it sounds easy. However, despite this difficulty, I’ve found it to be well worth the effort. On a very basic level, it is one direct way to elicit the relaxation response we’ve talked about in past posts (see here). And if it could eventually lead to some bliss state the yogis also talk about, bring it on!

In future posts we will discuss other meditation techniques, but for the holidays ahead, stick to the basics of simple breath awareness, done seated or in Savasana, and I’ll talk to you in the new year.

As I pass through yet another solstice and the modern winter holiday celebrations, I appreciate my own meditation practice, however sporadic it is at times. So I thought today would be a good day to begin introducing the topic of meditation on this blog.

Even trying to introduce the topic of meditation is a bit daunting, however, because there are many eastern traditions that have varied and unique approaches and emphases when they define meditation. So let’s narrow the scope and look at hatha yoga or even classical yoga, where we first find Patanjali in the Yoga Sutras placing dhyana or meditation within the context of the eight limbs of yoga, or the Ashtanga Yoga.

In this model, meditation is considered the second of two stages, beginning with dharana, or one-pointed concentration, and then moving onto dhyana, or continuous concentration or focus on an object. An analogy that Mr. Iyengar and others have used to explain this goes like this: If the mind were a water faucet and the object of my meditation was the bucket below it, when I first begin to focus, the water comes out in drops and moves towards the bucket, but with breaks in between, which represent distraction of the mind from the object. If my practice gets stronger and steadier, a time arrives when my focus is unbroken, represented as a continuous stream of water flowing toward the bucket. This is the stage of “meditation” or dhyana. I am still aware of “me” as the faucet, and the thing I am observing, the bucket, as separate from me, but I am really starting to understand what “bucket” is on a deep level.

|

| Mushroom at Silver Beach by Brad Gibson |

For us, the process begins on a more practical note, when in our first yoga asana practices we are encouraged to simply follow the flow of the breath with our minds to the exclusion of other possible things to focus on. This is essentially the first stage described above: dharana. Anyone who has tried this, if they are really honest, will admit how hard it is to stay on track. One of my teachers used to say that if you could follow the breath for three full cycles of in and out without another distracting thought breaking your concentration, you would reach enlightenment immediately—his way of saying that this is really hard to do, even though it sounds easy. However, despite this difficulty, I’ve found it to be well worth the effort. On a very basic level, it is one direct way to elicit the relaxation response we’ve talked about in past posts (see here). And if it could eventually lead to some bliss state the yogis also talk about, bring it on!

In future posts we will discuss other meditation techniques, but for the holidays ahead, stick to the basics of simple breath awareness, done seated or in Savasana, and I’ll talk to you in the new year.

Tuesday, December 20, 2011

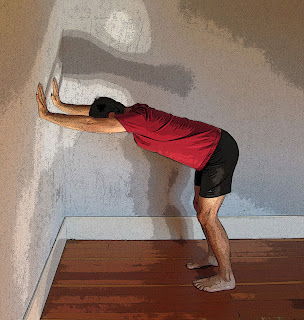

Featured Pose: Half-Dog Pose at the Wall

by Baxter and Nina

The featured pose this week is a version of the classic Downward-Facing Dog pose that is a bit easier to do than the full pose and does not require a clean floor or a prop other than a wall. It’s a fantastic allover stretch, opening your shoulders and stretching your arms, back, hips and legs (in the straight leg version). It also provides a good forward bend of your pelvis over your thighbones without bending in your lower back. It’s accessible to almost everyone, so it’s perfect for students who are new to yoga or who are recovering from an injury.

Half Dog Pose at the Wall is an excellent way to begin a yoga practice. And it’s also perfect as a single-pose practice when you need a break at work or while traveling. If you don’t have wall available, you can do the pose with your hands resting on a desktop or counter, or on the seat of a chair.

Baxter prescribes this pose for:

Bend your knees a bit and slowly walk your feet away from the wall. Keeping your hips positioned over your feet, gradually walk out until your arms are straight and form a long line with your torso and belly. Push your arms strongly towards the wall, while creating an upward lift from your knees to your hips.

You can gradually straighten your knees as long as it doesn't cause pain in your lower back.

Stay in the pose for 14-16 breaths, and then walk back toward wall to come up and out.

Cautions: Although this pose is good for most students, those with significant rotator cuff issues may have to work with a local teacher to find a good modification that does not aggravate their condition. If bending your wrists to 90 degrees is a problem, you can do the pose with just your fingertips on the wall.

Newer students should start out with about six breaths in the pose and work their way up to one to two minutes.

The featured pose this week is a version of the classic Downward-Facing Dog pose that is a bit easier to do than the full pose and does not require a clean floor or a prop other than a wall. It’s a fantastic allover stretch, opening your shoulders and stretching your arms, back, hips and legs (in the straight leg version). It also provides a good forward bend of your pelvis over your thighbones without bending in your lower back. It’s accessible to almost everyone, so it’s perfect for students who are new to yoga or who are recovering from an injury.

Half Dog Pose at the Wall is an excellent way to begin a yoga practice. And it’s also perfect as a single-pose practice when you need a break at work or while traveling. If you don’t have wall available, you can do the pose with your hands resting on a desktop or counter, or on the seat of a chair.

Baxter prescribes this pose for:

- low back pain

- releasing muscle tension due to stress

- an alternative to full Downward-Facing Dog for those with hand or wrist problems

- an alternative to full Downward-Facing Dog for those with cardiovascular or neurologic conditions, such as hypertension or vertigo

- an alternative to full Downward-Facing Dog for those with limited shoulder mobility due

- either to stiffness or injury

- an antidote stretch for working at a desk, driving, or traveling

Bend your knees a bit and slowly walk your feet away from the wall. Keeping your hips positioned over your feet, gradually walk out until your arms are straight and form a long line with your torso and belly. Push your arms strongly towards the wall, while creating an upward lift from your knees to your hips.

You can gradually straighten your knees as long as it doesn't cause pain in your lower back.

Stay in the pose for 14-16 breaths, and then walk back toward wall to come up and out.

Cautions: Although this pose is good for most students, those with significant rotator cuff issues may have to work with a local teacher to find a good modification that does not aggravate their condition. If bending your wrists to 90 degrees is a problem, you can do the pose with just your fingertips on the wall.

Newer students should start out with about six breaths in the pose and work their way up to one to two minutes.

Monday, December 19, 2011

Yoga Philosophy: Contentment

by Nina

“He who finds happiness only within, rest only within, light only within—that yogi having become one with nature attains oneness with Brahman.” —The Bhagavad Gita, trans. by Mohandas K. Ghandi

When I first started teaching, I was determined to find the right language to help my students come slowly out of Savasana (a bigger challenge than you might imagine!). Eventually I learned that repeating the word “slowly” three times (as in “slowly, slowly, slowly bend your knees and place the soles of your feet on the floor”) did the trick. My point? It’s simply that the language that you use can sometimes make all the difference.

I’m bringing this up today because I’ve been thinking about contentment, one of the qualities the Yoga Sutras encourages us to cultivate.

“2.42 From contentment and benevolence of consciousness come supreme happiness.” –Yoga Sutras, trans. by TKV Desikachar

“Contentment or the ability to be comfortable with what we have and what we do not have.” —TKV Desikachar

To me, this means that here are many unpleasant situations in your life that you cannot change, some minor (traffic jams, not being able to find something you need) and some major (death, divorce, loss of a job). And in these circumstances when you normally would react with anger, anxiety, envy, frustration, sorrow, you might be able to choose to react instead with contentment.

But another thing I’ve learned from teaching is that the words “happiness” and even “contentment” can be a confusing to people. How, students will say, can I be “content” when something bad happens? Or how, a person with depression, will ask, can just tell myself to be “happy?”

For myself, the answer was using different language: “I can be okay with this.” During the last four years, I’ve experienced a lot of loss: both my parents died and both my children moved thousands of miles away. But telling myself that, even while I was sad, I could be also okay with those circumstances did, in fact, help lead me toward contentment.

If you’ve been reading this blog for a while you’ll know that I’m a big fan of yoga’s stress reduction tools, including poses, breath techniques and meditation, for cultivating equanimity. But yoga philosophy has also been extremely helpful to me.

In our materialistic and success-oriented culture, we are bombarded with messages telling us we need to do more and buy more. So we become caught up in an endless cycle of desire and dissatisfaction, which benefits the economy but not necessarily our happiness. For me, yoga philosophy is the antidote. Although yoga promises freedom from the bondage of the unending cycle of desire and dissatisfaction, I can’t say I’m there yet. But at the very least, when I notice dissatisfaction taking over, I’ve learned to step back and remind myself there is a different point of view.

“2.42 From contentment, the highest happiness is attained.” —Yoga Sutras, trans. Edwin Bryant

“This sattvic happiness does not depend on external objects, which are vulnerable and fleeting, but is inherent in the mind when it is tranquil and content.” —Bryant’s commentary

“He who finds happiness only within, rest only within, light only within—that yogi having become one with nature attains oneness with Brahman.” —The Bhagavad Gita, trans. by Mohandas K. Ghandi

When I first started teaching, I was determined to find the right language to help my students come slowly out of Savasana (a bigger challenge than you might imagine!). Eventually I learned that repeating the word “slowly” three times (as in “slowly, slowly, slowly bend your knees and place the soles of your feet on the floor”) did the trick. My point? It’s simply that the language that you use can sometimes make all the difference.

I’m bringing this up today because I’ve been thinking about contentment, one of the qualities the Yoga Sutras encourages us to cultivate.

“2.42 From contentment and benevolence of consciousness come supreme happiness.” –Yoga Sutras, trans. by TKV Desikachar

“Contentment or the ability to be comfortable with what we have and what we do not have.” —TKV Desikachar

To me, this means that here are many unpleasant situations in your life that you cannot change, some minor (traffic jams, not being able to find something you need) and some major (death, divorce, loss of a job). And in these circumstances when you normally would react with anger, anxiety, envy, frustration, sorrow, you might be able to choose to react instead with contentment.

But another thing I’ve learned from teaching is that the words “happiness” and even “contentment” can be a confusing to people. How, students will say, can I be “content” when something bad happens? Or how, a person with depression, will ask, can just tell myself to be “happy?”

|

| Through the Mist by Brad Gibson |

If you’ve been reading this blog for a while you’ll know that I’m a big fan of yoga’s stress reduction tools, including poses, breath techniques and meditation, for cultivating equanimity. But yoga philosophy has also been extremely helpful to me.

In our materialistic and success-oriented culture, we are bombarded with messages telling us we need to do more and buy more. So we become caught up in an endless cycle of desire and dissatisfaction, which benefits the economy but not necessarily our happiness. For me, yoga philosophy is the antidote. Although yoga promises freedom from the bondage of the unending cycle of desire and dissatisfaction, I can’t say I’m there yet. But at the very least, when I notice dissatisfaction taking over, I’ve learned to step back and remind myself there is a different point of view.

“2.42 From contentment, the highest happiness is attained.” —Yoga Sutras, trans. Edwin Bryant

“This sattvic happiness does not depend on external objects, which are vulnerable and fleeting, but is inherent in the mind when it is tranquil and content.” —Bryant’s commentary

Wednesday, December 14, 2011

Friday Q&A: Sequencing Two Poses

Q: I love the variation of Viparita Karani with the chair. I also love Knees to Chest, which you featured in an earlier post. What I am wondering is should I do a pose in between these 2 as a transition or is it OK to go back & forth between the 2?

A: There’s no need to do any poses between these two, as they’re both gentle, symmetrical poses. It’s only when you are doing a deep forward bend, backbend, or twist that you might want to consider a counter-pose.

Can you go back and forth between the two? Personally, if I were going to sequence these two poses, I’d do the Knees to Chest pose (see here) first because moving with your breath is slightly stimulating. Even if you don't move with your breath in this pose, you are actively engaging your muscles, which makes this an active, rather than passive pose. I’d follow Knees to Chest pose with the Viparita Karani variation (see here) because this is a deeply relaxing passive pose, and it’s traditional to finish your practice in a state of relaxation. Put them together, and you’ve just created a nice little mini practice for winding down at the end of the day.

In general, a good way to sequence poses is in an arc like this:

1. Warm-up poses

2. Active poses

3. Counter poses and/or cool-down poses

4. Relaxation poses

—Nina

I agree that the poses are fine sequenced as Nina suggested, especially if you are ultimately trying to quiet the nervous system. However, if you needed a rest but wanted to do a mild stimulation of system prior to heading back into your day, you could reverse them. I don’t think any particular pose needs to go between them, but both would be a nice counter-pose sequence at the end of a back bend practice.

—Baxter

A: There’s no need to do any poses between these two, as they’re both gentle, symmetrical poses. It’s only when you are doing a deep forward bend, backbend, or twist that you might want to consider a counter-pose.

Can you go back and forth between the two? Personally, if I were going to sequence these two poses, I’d do the Knees to Chest pose (see here) first because moving with your breath is slightly stimulating. Even if you don't move with your breath in this pose, you are actively engaging your muscles, which makes this an active, rather than passive pose. I’d follow Knees to Chest pose with the Viparita Karani variation (see here) because this is a deeply relaxing passive pose, and it’s traditional to finish your practice in a state of relaxation. Put them together, and you’ve just created a nice little mini practice for winding down at the end of the day.

In general, a good way to sequence poses is in an arc like this:

1. Warm-up poses

2. Active poses

3. Counter poses and/or cool-down poses

4. Relaxation poses

—Nina

I agree that the poses are fine sequenced as Nina suggested, especially if you are ultimately trying to quiet the nervous system. However, if you needed a rest but wanted to do a mild stimulation of system prior to heading back into your day, you could reverse them. I don’t think any particular pose needs to go between them, but both would be a nice counter-pose sequence at the end of a back bend practice.

—Baxter

Yoga and Your Emotions

by Nina

I once bet an old friend of mine, a long-time yoga student who expressed some doubt when I told him that yoga poses can have strong effects on our emotions, that I could change his mood by putting him in a yoga pose. He said, “You’re on!” So what I did was set him up in a supported form of Seated Forward Bend (Paschimottanasana) and left him there for three minutes (the amount of time needed for most supported poses to really take effect). When I told him it was time for him to come out the pose and he slowly lifted his head, I knew just by the look on his face—you know, that classic “yoga” look—that I’d won the bet hands down. And my friend did, in fact, concede quite gracefully, because the quieting power of a long forward bend (if you are set up comfortably) was undeniable.

Yes, various yoga poses and practices can have a strong effect on your moods and emotions, and this is something you should take into consideration when you practice on your own. I decided to write about this subject today because earlier this week another friend was surprised to learn that doing Sun Salutations before bed affected her ability to sleep. Knowing that certain poses like Sun Salutations and standing poses are stimulating can not only help you chose which poses to do at a particular time of time, but when you know something about how the poses effect you in general, you can actually practice to balance your emotions.

So today I’ve grouped the yoga poses into general categories, and for each category, I’ll list some of the typical emotional effects. In the end, however, don’t just take my word for it. You should always rely on your personal experience to guide you. Baxter and I once had a student who said that twists made her sleepy. That’s not the traditional view of how twists effect us, but if this woman felt they made her sleepy, well, that’s what they did!

Standing Poses. These are considered to be very grounding poses, which immediately engage your body-mind and bring you into the present moment. So they are good poses to do when you are worried and distracted or agitated. Standing poses are also stimulating, because being upright raises your blood pressure and increases your heart rate (ha, ha, the reverse of being inverted). So while these are great poses to do in the morning or afternoon, these are not good poses to do before bedtime if you have trouble sleeping.

Sun Salutations. Poses that are linked together with the breath, including Sun Salutations, moving from Paschimottanasna to Halasana and back, and even just moving from Tadasana to Uttanasana and back, can energize your emotional body and can help lift you out of lethargy, depression, or sadness. Like standing poses, Sun Salutations are stimulating. Moving with your breath increases your oxygen intake and up to standing and then back down again can raise your blood pressure. So like standing poses, Sun Salutations are great in the morning or afternoon, but not good to do before bedtime if you have trouble sleeping.

Backbends. These are considered to be energizing, uplifting poses. They may help create more energy when you are tired and may help lift you out of depression or sadness. On the negative side, they may actually make you too hyper if you are already nervous, and some people have difficulty falling asleep after practicing backbends. Because they literally open the heart area, they may cause strong emotions to arise—sometimes people find themselves crying after doing a lot of backbends. One way to access the energizing, uplifting quality of these poses without over-stimulating yourself it is to do passive, supported backbends.

Twists. These are considered to be cleansing poses. They can help release stress from your body-mind. On the negative side, twists may also release difficult feelings or emotions, so that they may actually leave you feeling a bit yucky—that’s a technical term—although that has never happened to me.

Forward Bends. These are considered to be quieting, introverted poses. They are restful poses that can calm you down when you are feeling agitated or hyper and rest you when you are feeling fatigued. On the negative side, the inward-turning quality of the poses may cause you to brood or feel claustrophobic. Supported versions of these poses that remove the physical resistance from the pose can be extremely quieting and calming.

Inverted Poses. These poses are considered to be soothing and centering poses. Although Headstand is a fiery pose (it warms you physically), it is also very calming. And any pose where you head is on the ground, such as Supported Downward-Facing Dog, Supported Standing Forward Bend, and Supported Wide Angle Standing Forward Bend, is considered to have the same benefits and can be substituted for Headstand. Shoulderstand—if it is at all comfortable for you—is more cooling than Headstand and is considered the ultimate soothing pose (the mother of all poses). Viparita Karani is also very soothing for almost everybody. I think a good reason to do the work to become comfortable with Headstand and Shoulderstand is because the benefits they provide are so valuable.

Arm Balances. Handstand and the other arm balances fully engage your body-mind as they demand your immediate presence of mind. This can help distract you from concerns outside the yoga room and therefore lift your spirits or at least give you a break from your obsessions. (Patricia Walden recommends them for depression for people for whom backbends are very easy.)

Hip Openers and Seated Poses. These poses are considered to be very grounding and centering. They seem to release tension, especially from the legs, and bring you into the present moment. On the negative side, opening your hips can sometimes feel really yucky—both mentally and physically—who knows why?—and you might not feel up to it some days.

Readers, what are your thoughts about the emotional effects of various yoga poses?

I once bet an old friend of mine, a long-time yoga student who expressed some doubt when I told him that yoga poses can have strong effects on our emotions, that I could change his mood by putting him in a yoga pose. He said, “You’re on!” So what I did was set him up in a supported form of Seated Forward Bend (Paschimottanasana) and left him there for three minutes (the amount of time needed for most supported poses to really take effect). When I told him it was time for him to come out the pose and he slowly lifted his head, I knew just by the look on his face—you know, that classic “yoga” look—that I’d won the bet hands down. And my friend did, in fact, concede quite gracefully, because the quieting power of a long forward bend (if you are set up comfortably) was undeniable.

|

| La Sagrada Familia (a detail) by Brad Gibson |

So today I’ve grouped the yoga poses into general categories, and for each category, I’ll list some of the typical emotional effects. In the end, however, don’t just take my word for it. You should always rely on your personal experience to guide you. Baxter and I once had a student who said that twists made her sleepy. That’s not the traditional view of how twists effect us, but if this woman felt they made her sleepy, well, that’s what they did!

Standing Poses. These are considered to be very grounding poses, which immediately engage your body-mind and bring you into the present moment. So they are good poses to do when you are worried and distracted or agitated. Standing poses are also stimulating, because being upright raises your blood pressure and increases your heart rate (ha, ha, the reverse of being inverted). So while these are great poses to do in the morning or afternoon, these are not good poses to do before bedtime if you have trouble sleeping.

Sun Salutations. Poses that are linked together with the breath, including Sun Salutations, moving from Paschimottanasna to Halasana and back, and even just moving from Tadasana to Uttanasana and back, can energize your emotional body and can help lift you out of lethargy, depression, or sadness. Like standing poses, Sun Salutations are stimulating. Moving with your breath increases your oxygen intake and up to standing and then back down again can raise your blood pressure. So like standing poses, Sun Salutations are great in the morning or afternoon, but not good to do before bedtime if you have trouble sleeping.

Backbends. These are considered to be energizing, uplifting poses. They may help create more energy when you are tired and may help lift you out of depression or sadness. On the negative side, they may actually make you too hyper if you are already nervous, and some people have difficulty falling asleep after practicing backbends. Because they literally open the heart area, they may cause strong emotions to arise—sometimes people find themselves crying after doing a lot of backbends. One way to access the energizing, uplifting quality of these poses without over-stimulating yourself it is to do passive, supported backbends.

Twists. These are considered to be cleansing poses. They can help release stress from your body-mind. On the negative side, twists may also release difficult feelings or emotions, so that they may actually leave you feeling a bit yucky—that’s a technical term—although that has never happened to me.

Forward Bends. These are considered to be quieting, introverted poses. They are restful poses that can calm you down when you are feeling agitated or hyper and rest you when you are feeling fatigued. On the negative side, the inward-turning quality of the poses may cause you to brood or feel claustrophobic. Supported versions of these poses that remove the physical resistance from the pose can be extremely quieting and calming.

Inverted Poses. These poses are considered to be soothing and centering poses. Although Headstand is a fiery pose (it warms you physically), it is also very calming. And any pose where you head is on the ground, such as Supported Downward-Facing Dog, Supported Standing Forward Bend, and Supported Wide Angle Standing Forward Bend, is considered to have the same benefits and can be substituted for Headstand. Shoulderstand—if it is at all comfortable for you—is more cooling than Headstand and is considered the ultimate soothing pose (the mother of all poses). Viparita Karani is also very soothing for almost everybody. I think a good reason to do the work to become comfortable with Headstand and Shoulderstand is because the benefits they provide are so valuable.

Arm Balances. Handstand and the other arm balances fully engage your body-mind as they demand your immediate presence of mind. This can help distract you from concerns outside the yoga room and therefore lift your spirits or at least give you a break from your obsessions. (Patricia Walden recommends them for depression for people for whom backbends are very easy.)

Hip Openers and Seated Poses. These poses are considered to be very grounding and centering. They seem to release tension, especially from the legs, and bring you into the present moment. On the negative side, opening your hips can sometimes feel really yucky—both mentally and physically—who knows why?—and you might not feel up to it some days.

Readers, what are your thoughts about the emotional effects of various yoga poses?

Tuesday, December 13, 2011

Interview with Vickie Russell Bell, Continued: Teaching Yoga to Students with Parkinson's

Baxter: Can you talk a bit about what sort of experience or training would be optimal for a teacher out there thinking about doing this sort of class for folks with Parkinson’s?

Vickie: Teachers interested in working with PWPD need to have a strong background in teaching asana and adapting classic poses. Assisting a teacher who works with disabilities or special populations (or even someone who is adept at working with seniors) would be very useful. If a teacher is interested in eventually working with a group, starting solo with a PD student who is mobile and only slightly limited might help her begin to understand this population.

There are often local PD organizations that offer classes or info sessions for those interested in furthering their knowledge. I am currently training a number of yoga teachers who want to take this work into the community and I hope to expand this educational opportunity further.

Baxter: And final advice to either students with Parkinson’s, or teachers interested in working with this population?

Vickie: The thing that drives my success in working with this population is this motto: Teach to their possibility, not their disability! Be willing to be light, to play ant, to constantly continue to learn.

Vickie Russell Bell was born and raised in Ohio, and is a journalist by education. She teaches yoga because she loves to. Her intention is to help her students increase their level of daily awareness through their body, breath and experience. She is a graduate of the Piedmont Yoga Studio Advanced Training Program and is a certified “Relax and Renew Trainer” through Judith Lasater’s accredited program. See here for more information.

Vickie: Teachers interested in working with PWPD need to have a strong background in teaching asana and adapting classic poses. Assisting a teacher who works with disabilities or special populations (or even someone who is adept at working with seniors) would be very useful. If a teacher is interested in eventually working with a group, starting solo with a PD student who is mobile and only slightly limited might help her begin to understand this population.

There are often local PD organizations that offer classes or info sessions for those interested in furthering their knowledge. I am currently training a number of yoga teachers who want to take this work into the community and I hope to expand this educational opportunity further.

Baxter: And final advice to either students with Parkinson’s, or teachers interested in working with this population?

Vickie: The thing that drives my success in working with this population is this motto: Teach to their possibility, not their disability! Be willing to be light, to play ant, to constantly continue to learn.

Vickie Russell Bell was born and raised in Ohio, and is a journalist by education. She teaches yoga because she loves to. Her intention is to help her students increase their level of daily awareness through their body, breath and experience. She is a graduate of the Piedmont Yoga Studio Advanced Training Program and is a certified “Relax and Renew Trainer” through Judith Lasater’s accredited program. See here for more information.

Interview with Vickie Russell Bell: Yoga for Parkinson's Disease

In October, we were fortunate to have long-time yoga teacher and yoga writer Richard Rosen contribute a post about his personal journey with Parkinson’s Disease and the recommendations he has for working with the condition. This month, I am pleased to share with you an interview with another yoga teacher, Vickie Russell Bell, who has been involved in serving the Parkinson’s community for several years now. You can learn more about her teaching here.

Baxter: Vickie, I know that you have been offering a Parkinson’s Yoga Class at Piedmont Yoga Studio in Oakland for some time now. How did that come about, and what’s the class like?

Vickie: I’ve been teaching a yoga class for people with Parkinson’s Disease (PWPD) for a little more than three years now. I started off assisting Richard Rosen, teaching about 8-10 students, and then took over leading the classes. I now offer two classes weekly at Piedmont Yoga Studio through a local organization called PD Active! In a given week there are usually 12-18 participants per class. These students have varying physical abilities. I have two assistants helping in each class.

As Richard Rosen stated in a previous post about PD (see here): it is a progressive degenerative disorder of the central nervous system. Common physical symptoms are loss of muscular flexibility (PWPD become very stiff), loss of balance, loss of strength and often a noticeable resting tremor. Sometimes people who have been diagnosed with Parkinson’s are in denial, resentment or rejection of their condition. PD affects the body, mind and spirit and needs to be looked at holistically. Asana practice done regularly can help students to cultivate and refine their body awareness so as to work productively with some of these symptoms.

My students with Parkinson’s definitely need extra attention during classes. I attempt to adapt what I’m teaching in my public classes that week for the classes (for example, Downward Dog with hands on a chair seat, Warrior I with the front knee supported by a block and the wall, Bakasana (Crane pose) lying on the back). Often in class there is an extra emphasis on keeping the feet stretched, open and supple to increase awareness of the base, on balance, on opening the upper back/chest/lungs, and on restorative poses (PWPD are often taking various medications that can make them fatigued or affect sleep adversely).

Baxter: Can you share with our readers any observations of the benefits your students have discovered by regular attendance in your class?

Vickie: I can do even better! Here is some testimonial directly from one of mty PD Active yoga students:

“The yoga exercise class has helped me immensely and I feel it is due mostly to stretching of the muscles. Parkinson’s causes atrophy in our muscles and the yoga exercises are a direct hit against that atrophy. I walk straighter and breathe properly when I walk now. Learning to breathe properly in the yoga class has helped my freezing of feet problem as well. When my feet freeze now I stop, breathe, relax and off I go again. Before, I would go into panic mode, struggle and usually fall. I have had fewer falls since I started the yoga class. I used to fall about three times a week and now it is about twice a month and that’s usually due to my own inability to breathe properly and stay relaxed. Yoga has added to the quality of my life.”

Baxter: In Richard’s post, he mentioned the benefits of supported backbend over a bolster. Where do you see that pose fitting in, and what are two or three other essential poses you find helpful for your classes?

Vickie: I often incorporate the backbend over a bolster that Richard described in my classes. My students also love supported twists over a bolster as well as a Viparita Karani variation. Legs up the Wall is difficult for many Parkinson’s students due to tight hips and hamstrings, and rounded upper backs. So this is how I teach the Viparita Karani variation:

Fold two long, single fold blankets (Shoulderstand size in half long ways) and place them on the floor in front of a chair seat. Have the student sit with their tailbone right on the front edge of the blankets and lie back so that the blankets are perpendicular to the spine and support the lumbar curve and back of the pelvis. Some PD students may need help lying back safely, or may need help adjusting the blankets. The student then hooks the back of their knees on the front edge of the chair seat, resting the calves on the seat. If your student has a rounded upper back they might benefit from a lift under their head so that the chin and forehead are on the same level. Here's a photograph from one of my classes of a student in the pose:

This pose allows the low back (lumbar spine) to have a neutral curve or for some a slight backbend and allows the shoulders and chest to gently open. This can be a delicious pose for someone who spends most of their day with the head and shoulders hunched forward! I also teach PWPD adaptations of many standing poses and other beneficial active poses.

Tune in tomorrow for the second half of Baxter's interview with Vickie Russell Bell, in which she will talk about how to teach students with Parkinson's Disease.

Baxter: Vickie, I know that you have been offering a Parkinson’s Yoga Class at Piedmont Yoga Studio in Oakland for some time now. How did that come about, and what’s the class like?

Vickie: I’ve been teaching a yoga class for people with Parkinson’s Disease (PWPD) for a little more than three years now. I started off assisting Richard Rosen, teaching about 8-10 students, and then took over leading the classes. I now offer two classes weekly at Piedmont Yoga Studio through a local organization called PD Active! In a given week there are usually 12-18 participants per class. These students have varying physical abilities. I have two assistants helping in each class.

As Richard Rosen stated in a previous post about PD (see here): it is a progressive degenerative disorder of the central nervous system. Common physical symptoms are loss of muscular flexibility (PWPD become very stiff), loss of balance, loss of strength and often a noticeable resting tremor. Sometimes people who have been diagnosed with Parkinson’s are in denial, resentment or rejection of their condition. PD affects the body, mind and spirit and needs to be looked at holistically. Asana practice done regularly can help students to cultivate and refine their body awareness so as to work productively with some of these symptoms.

My students with Parkinson’s definitely need extra attention during classes. I attempt to adapt what I’m teaching in my public classes that week for the classes (for example, Downward Dog with hands on a chair seat, Warrior I with the front knee supported by a block and the wall, Bakasana (Crane pose) lying on the back). Often in class there is an extra emphasis on keeping the feet stretched, open and supple to increase awareness of the base, on balance, on opening the upper back/chest/lungs, and on restorative poses (PWPD are often taking various medications that can make them fatigued or affect sleep adversely).

Baxter: Can you share with our readers any observations of the benefits your students have discovered by regular attendance in your class?

Vickie: I can do even better! Here is some testimonial directly from one of mty PD Active yoga students:

“The yoga exercise class has helped me immensely and I feel it is due mostly to stretching of the muscles. Parkinson’s causes atrophy in our muscles and the yoga exercises are a direct hit against that atrophy. I walk straighter and breathe properly when I walk now. Learning to breathe properly in the yoga class has helped my freezing of feet problem as well. When my feet freeze now I stop, breathe, relax and off I go again. Before, I would go into panic mode, struggle and usually fall. I have had fewer falls since I started the yoga class. I used to fall about three times a week and now it is about twice a month and that’s usually due to my own inability to breathe properly and stay relaxed. Yoga has added to the quality of my life.”

Baxter: In Richard’s post, he mentioned the benefits of supported backbend over a bolster. Where do you see that pose fitting in, and what are two or three other essential poses you find helpful for your classes?

Vickie: I often incorporate the backbend over a bolster that Richard described in my classes. My students also love supported twists over a bolster as well as a Viparita Karani variation. Legs up the Wall is difficult for many Parkinson’s students due to tight hips and hamstrings, and rounded upper backs. So this is how I teach the Viparita Karani variation:

Fold two long, single fold blankets (Shoulderstand size in half long ways) and place them on the floor in front of a chair seat. Have the student sit with their tailbone right on the front edge of the blankets and lie back so that the blankets are perpendicular to the spine and support the lumbar curve and back of the pelvis. Some PD students may need help lying back safely, or may need help adjusting the blankets. The student then hooks the back of their knees on the front edge of the chair seat, resting the calves on the seat. If your student has a rounded upper back they might benefit from a lift under their head so that the chin and forehead are on the same level. Here's a photograph from one of my classes of a student in the pose:

|

| Viparita Karani variation (also called Easy Inverted pose) |

Tune in tomorrow for the second half of Baxter's interview with Vickie Russell Bell, in which she will talk about how to teach students with Parkinson's Disease.

Monday, December 12, 2011

Featured Pose: Knees to Chest Pose (Apanasana)

by Baxter and Nina

Knees to Chest pose is a great way to warm up at the beginning of a practice or to cool down at the end of a practice, especially after a backbend or forward bend practice. This pose allows you to check in with the tightness or openness of your hip and buttock muscles and soft tissues, as you gently massage your lower back and abdomen. Because your knees are bent, the tension on the hamstring muscles is greatly reduced, making it safer than straight leg stretches for those nursing a sore or injured lower back. It’s very easy to do, doesn’t require props, and doesn’t take up much space, so this pose is one you can do almost any time or anywhere for quick relief of low back pain or discomfort after sitting for long periods of time, such as at a desk, in a car, or on an airplane.

This pose goes by different names Sanskrit names, depending on the yoga lineage. In the Krishnamacharya tradition, it is called Apanasana, with apana referring to the downward moving inner energetic wind of the body. So the pose is associated with anything that needs to exit the body from the perineum, including waste from the GI tract, as well as reproduction functions (it is sometimes recommended for menstrual irregularity, although Baxter knows of no evidence to support this). In other traditions, the pose is called Pavanmuktasana, which means wind-relieving pose. That name is self explanatory!

Baxter prescribes this pose for:

• low back relief

• tight hips

• GI conditions where sluggishness is a problem (such as constipation)

• general relaxation prior to Savasana

Instructions: Lie on your back with your knees bent and feet on floor.

Next, hold onto your knees with your hands, keeping your arms straight. On an inhalation, lift your feet up just a bit. Completely relax your leg muscles and let your arms do all the work.

Then, on your exhalation, bend your elbows and draw your knees toward your chest.

On your inhalation, straighten your arms and release your knees to the starting position. Repeat six times, moving with your breath.

Baxter recommends the dynamic version of this pose (moving with your breath) for low back pain, but if you are using the pose for other reasons and you prefer holding the pose for a longer period of time, you can keep your knees to your chest for 30 seconds to one minute.

Cautions: If you have knee problems, hold your hands behind your knees (between your calves and thighs). If the bones of soft tissues of your lower back or pelvis are sensitive, lie on a folded blanket or other padding.

Knees to Chest pose is a great way to warm up at the beginning of a practice or to cool down at the end of a practice, especially after a backbend or forward bend practice. This pose allows you to check in with the tightness or openness of your hip and buttock muscles and soft tissues, as you gently massage your lower back and abdomen. Because your knees are bent, the tension on the hamstring muscles is greatly reduced, making it safer than straight leg stretches for those nursing a sore or injured lower back. It’s very easy to do, doesn’t require props, and doesn’t take up much space, so this pose is one you can do almost any time or anywhere for quick relief of low back pain or discomfort after sitting for long periods of time, such as at a desk, in a car, or on an airplane.

This pose goes by different names Sanskrit names, depending on the yoga lineage. In the Krishnamacharya tradition, it is called Apanasana, with apana referring to the downward moving inner energetic wind of the body. So the pose is associated with anything that needs to exit the body from the perineum, including waste from the GI tract, as well as reproduction functions (it is sometimes recommended for menstrual irregularity, although Baxter knows of no evidence to support this). In other traditions, the pose is called Pavanmuktasana, which means wind-relieving pose. That name is self explanatory!

Baxter prescribes this pose for:

• low back relief

• tight hips

• GI conditions where sluggishness is a problem (such as constipation)

• general relaxation prior to Savasana

Instructions: Lie on your back with your knees bent and feet on floor.

Next, hold onto your knees with your hands, keeping your arms straight. On an inhalation, lift your feet up just a bit. Completely relax your leg muscles and let your arms do all the work.

Then, on your exhalation, bend your elbows and draw your knees toward your chest.

On your inhalation, straighten your arms and release your knees to the starting position. Repeat six times, moving with your breath.

Baxter recommends the dynamic version of this pose (moving with your breath) for low back pain, but if you are using the pose for other reasons and you prefer holding the pose for a longer period of time, you can keep your knees to your chest for 30 seconds to one minute.

Cautions: If you have knee problems, hold your hands behind your knees (between your calves and thighs). If the bones of soft tissues of your lower back or pelvis are sensitive, lie on a folded blanket or other padding.

Friday, December 9, 2011

Friday Q&A: Restorative Yoga

Q: Thanks to your blog, I’ve been practicing Legs Up the Wall pose on a regular basis now, and I just love it. However, I have a friend who can’t do inversions due to blood pressure concerns. What are some relaxing poses that she can do?

A: Restorative yoga is perfect for someone like your friend, as well as anyone who is sick, stressed out, or low on energy, or who just wants to experience a soothing practice. Restorative yoga is a form of yoga that was specially designed to provide deep rest and relaxation. In restorative yoga, you use props to support yourself in the shape of a classic yoga pose, including forward bends, backbends, side stretches, twists, and inversions. For example, in Child’s Pose, rather than folding forward all the way on to the floor, you use a bolster or stack of folded blankets to support your entire front body.

The props you use in restorative yoga not only make the pose more comfortable but they take the effort out of the pose. Rather than using your muscles to hold you in the shape of a pose as you would normally, the props hold you in the pose so you can simply let your muscles relax. With your muscles completely relaxed, you can then turn your attention inward, focusing on your breath, physical sensations, or any other object of meditation, which allows the relaxation response to switch on.

Now you might ask, why would you go through the trouble to put yourself into a restorative yoga pose when you can just do Savasana (Corpse pose)? In Savasana your body is in an anatomically neutral position, so that no muscles are being released or stretched. In a restorative pose, however, you still receive many of the benefits of the pose itself. For example, in a restorative backbend, you are opening your chest and stretching many of the muscles that become tight after driving long distances or sitting hunched forward at a desk all day. Passively stretching your muscles as your relax increases your feeling of relaxation, as some of the stress you have been holding in your body is gently released. And because you are completely comfortable and relaxed, you can stay in the pose for much longer amounts of time. So restorative poses are actually a good way to work on flexibility, as well as relaxation.

We definitely plan to introduce some restorative yoga poses and sequences on this blog in the future, but until then, three of the books on our list of recommendations yesterday (see here) are good resources for information on restorative yoga: Moving Toward Balance, Relax & Renew, and The Woman’s Book of Yoga and Health.

—Nina

A: Restorative yoga is perfect for someone like your friend, as well as anyone who is sick, stressed out, or low on energy, or who just wants to experience a soothing practice. Restorative yoga is a form of yoga that was specially designed to provide deep rest and relaxation. In restorative yoga, you use props to support yourself in the shape of a classic yoga pose, including forward bends, backbends, side stretches, twists, and inversions. For example, in Child’s Pose, rather than folding forward all the way on to the floor, you use a bolster or stack of folded blankets to support your entire front body.

|

| Standard Child's Pose |

|

| Restorative Child's Pose |

Now you might ask, why would you go through the trouble to put yourself into a restorative yoga pose when you can just do Savasana (Corpse pose)? In Savasana your body is in an anatomically neutral position, so that no muscles are being released or stretched. In a restorative pose, however, you still receive many of the benefits of the pose itself. For example, in a restorative backbend, you are opening your chest and stretching many of the muscles that become tight after driving long distances or sitting hunched forward at a desk all day. Passively stretching your muscles as your relax increases your feeling of relaxation, as some of the stress you have been holding in your body is gently released. And because you are completely comfortable and relaxed, you can stay in the pose for much longer amounts of time. So restorative poses are actually a good way to work on flexibility, as well as relaxation.

We definitely plan to introduce some restorative yoga poses and sequences on this blog in the future, but until then, three of the books on our list of recommendations yesterday (see here) are good resources for information on restorative yoga: Moving Toward Balance, Relax & Renew, and The Woman’s Book of Yoga and Health.

—Nina

Thursday, December 8, 2011

Shopping List: Yoga Books We Can’t Live Without

by Nina and Baxter

For most people who practice yoga at home, yoga books are indispensable. When you have questions about poses, you can look at photographs. When you don’t know what to practice, you can find a sequence to try. When you need inspiration, you can turn to classical yoga philosophy or read advice and wisdom from any number of well-known teachers. At Nina's house, they even have two copies of the same book (which they fondly refer to as “The Red Leotard Book”), so she and her husband can be sure of having a copy with them for reference when they practice.

Since it’s, well, the time of year when you are probably wracking your brains trying to finish your own lists, Baxter and I thought this might be a good time for us to list our yoga favorite yoga books for your shopping pleasure. So without further ado:

Nina’s Picks

1. Yoga the Iyengar Way, Silva, Mira, and Shyam Mehta, Alfred A. Knopf. When you have questions about the alignment for a pose and want to see a photograph of it, this is by far the best resource. Beautiful!

2. The Woman’s Book of Yoga and Health, Linda Sparrowe with Patricia Walden, Shambhala Publications. By far, my most used yoga book. I love the sequences, and the propping Patricia recommends is some of the most helpful and useable.

3. Yoga: Awakening the Inner Body, Donald Moyer, Rodmell Press. If you want to read alignment details about the classic yoga poses, this book does a great job of explaining them (and just happens to be by my favorite yoga teacher).

4. Relax & Renew, Judith Lasater, Rodmell Press. The best introduction to restorative yoga, with a large number of sequences for different conditions.

5. The Yoga of Breath, Richard Rosen, Shambhala Publications. A very good introduction to yogic breathing.

6. The Yoga Tradition, Georg Feuerstein, Hohm Press. A scholarly, somewhat intimidating but very worthwhile history of yoga, including translations of many seminal yoga texts.

7. Light on the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali, B.K.S. Iyengar, HarperCollins. Among the many different translations with commentaries, this is one of the most accessible.

8. The Bhagavad Gita, translated by Juan Mascaro, Penguin Books. This translation is powerful and poetic, and the introduction is very helpful.

Baxter’s Picks

1. Moving Toward Balance, Rodney Yee with Nina Zolotow, Rodale Books. With three versions of every pose, sequences designed for the home practitioner, and advice about home practice, this book is the one I recommend to anyone who wants to practice at home.

2. The Heart of Yoga, T.K.V. Desikachar, Inner Traditions. A wonderful introduction to the yoga of the teacher who developed so much of what we now practice in the west.

3. Yoga and the Quest for the True Self, Stephen Cope, Bantam. A lively, easy-to-read introduction to basic yoga philosophy.

4. The Wisdom of Yoga: A Seeker’s Guide to Extraordinary Living, Stephen Cope, Bantam. A very accessible introduction to the philosophy of the Yoga Sutras.

5. The Yoga Sutras: An Essential Guide to the Heart of Yoga Philosophy, Nicholai Bachman, Sounds True, Inc. A true splurge, this complete kit features seven CDs, a 200-page workbook with color illustrations, and 51 meditation cards.

6. Chants of a Lifetime: Searching for a Heart of Gold, Krishna Das, Hay House, Inc. For those who want to learn something about bhakti yoga (the yoga of devotion), this book includes a bonus CD of chanting.

For most people who practice yoga at home, yoga books are indispensable. When you have questions about poses, you can look at photographs. When you don’t know what to practice, you can find a sequence to try. When you need inspiration, you can turn to classical yoga philosophy or read advice and wisdom from any number of well-known teachers. At Nina's house, they even have two copies of the same book (which they fondly refer to as “The Red Leotard Book”), so she and her husband can be sure of having a copy with them for reference when they practice.

|

| Yes, We Have 2 Copies of This Book |

Since it’s, well, the time of year when you are probably wracking your brains trying to finish your own lists, Baxter and I thought this might be a good time for us to list our yoga favorite yoga books for your shopping pleasure. So without further ado:

Nina’s Picks

1. Yoga the Iyengar Way, Silva, Mira, and Shyam Mehta, Alfred A. Knopf. When you have questions about the alignment for a pose and want to see a photograph of it, this is by far the best resource. Beautiful!

2. The Woman’s Book of Yoga and Health, Linda Sparrowe with Patricia Walden, Shambhala Publications. By far, my most used yoga book. I love the sequences, and the propping Patricia recommends is some of the most helpful and useable.

3. Yoga: Awakening the Inner Body, Donald Moyer, Rodmell Press. If you want to read alignment details about the classic yoga poses, this book does a great job of explaining them (and just happens to be by my favorite yoga teacher).

4. Relax & Renew, Judith Lasater, Rodmell Press. The best introduction to restorative yoga, with a large number of sequences for different conditions.

5. The Yoga of Breath, Richard Rosen, Shambhala Publications. A very good introduction to yogic breathing.

6. The Yoga Tradition, Georg Feuerstein, Hohm Press. A scholarly, somewhat intimidating but very worthwhile history of yoga, including translations of many seminal yoga texts.

7. Light on the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali, B.K.S. Iyengar, HarperCollins. Among the many different translations with commentaries, this is one of the most accessible.

8. The Bhagavad Gita, translated by Juan Mascaro, Penguin Books. This translation is powerful and poetic, and the introduction is very helpful.

Baxter’s Picks

1. Moving Toward Balance, Rodney Yee with Nina Zolotow, Rodale Books. With three versions of every pose, sequences designed for the home practitioner, and advice about home practice, this book is the one I recommend to anyone who wants to practice at home.

2. The Heart of Yoga, T.K.V. Desikachar, Inner Traditions. A wonderful introduction to the yoga of the teacher who developed so much of what we now practice in the west.

3. Yoga and the Quest for the True Self, Stephen Cope, Bantam. A lively, easy-to-read introduction to basic yoga philosophy.

4. The Wisdom of Yoga: A Seeker’s Guide to Extraordinary Living, Stephen Cope, Bantam. A very accessible introduction to the philosophy of the Yoga Sutras.

5. The Yoga Sutras: An Essential Guide to the Heart of Yoga Philosophy, Nicholai Bachman, Sounds True, Inc. A true splurge, this complete kit features seven CDs, a 200-page workbook with color illustrations, and 51 meditation cards.

6. Chants of a Lifetime: Searching for a Heart of Gold, Krishna Das, Hay House, Inc. For those who want to learn something about bhakti yoga (the yoga of devotion), this book includes a bonus CD of chanting.

Wednesday, December 7, 2011

Your Key to Your Nervous System: Your Breath

by Nina

Have you ever wondered why you tend to yawn when you’re sleepy? Well, a yawn is a great big inhalation. And because your heart rate tends to speed up on your inhalation, that yawn in the middle of that boring lecture or business meeting is little message to your nervous system: wake up! On the other hand, when you are upset about something, you tend to sigh. That sigh—try one!—is an extra long exhalation. Because your heart rate tends to slow on your exhalation, that sigh while you are feeling emotional turmoil or are just stuck in traffic is a little message to your nervous system: take it easy, buddy, slow down a bit.

Your autonomic nervous system is the part of your nervous system that controls the functions of your body, such as digestion, heartbeat, blood pressure, and breathing, that are “involuntary,” meaning the functions that you don’t have to think about. The autonomic nervous system is also the part of your nervous system that sends you into stress mode (fight or flight) and that triggers the relaxation response. And while you cannot tell your nervous system directly to slow your heart beat, digest your food more quickly (that would be nice, wouldn’t it?), or to start relaxing right this minute, you can control your breath.

Think about it: even though you breathe without thinking about it, you can intentionally hold your breath, speed up your breath, slow down your breath, breathe through one nostril instead of the other, and so on. And this ability to alter your breathing is what gives you the key to your nervous system, providing you with some control over its “involuntary” functions.

In my post on the stress response (see "Chronic Stress: An Introduction"), I mentioned that in stress mode your body uses more oxygen (for fighting or fleeing) while in relaxation mode your body needs less oxygen (for resting and digesting). It turns out that by intentionally taking in more oxygen (either by speeding up your breath or by lengthening your inhalation) you can stimulate your nervous system and that by taking in less oxygen (by slowing your breath or lengthening your exhalation), you can calm yourself down. It’s that simple. (See "Stress Test" for my example of using breath practice to stay calm during oral surgery.)

Yogic breath practices have evolved over thousands of years as yogis experimented on themselves and passed on their discoveries their students. And while some schools of yoga teach yogic breath practices (pranayama) to beginners, the type of yoga that I’m trained in, Iyengar style, considers breath practices to be so powerful that pranayama is introduced very gradually.

We’ll be introducing some simple breath practices in the coming weeks, but until then start by tuning into your breath throughout the day. When you’re standing in a long line at the post office, fighting the crowds at the grocery store, or are stuck in traffic, are you taking quick breaths, deep breaths or sighing? When you’re taking a hot bubble bath, petting your dog, or chatting with your partner after a good dinner, are you taking slow breaths, shallow breaths, or—oops!—yawning?

Have you ever wondered why you tend to yawn when you’re sleepy? Well, a yawn is a great big inhalation. And because your heart rate tends to speed up on your inhalation, that yawn in the middle of that boring lecture or business meeting is little message to your nervous system: wake up! On the other hand, when you are upset about something, you tend to sigh. That sigh—try one!—is an extra long exhalation. Because your heart rate tends to slow on your exhalation, that sigh while you are feeling emotional turmoil or are just stuck in traffic is a little message to your nervous system: take it easy, buddy, slow down a bit.

Your autonomic nervous system is the part of your nervous system that controls the functions of your body, such as digestion, heartbeat, blood pressure, and breathing, that are “involuntary,” meaning the functions that you don’t have to think about. The autonomic nervous system is also the part of your nervous system that sends you into stress mode (fight or flight) and that triggers the relaxation response. And while you cannot tell your nervous system directly to slow your heart beat, digest your food more quickly (that would be nice, wouldn’t it?), or to start relaxing right this minute, you can control your breath.

Think about it: even though you breathe without thinking about it, you can intentionally hold your breath, speed up your breath, slow down your breath, breathe through one nostril instead of the other, and so on. And this ability to alter your breathing is what gives you the key to your nervous system, providing you with some control over its “involuntary” functions.

|

| Tide Under First Bridge by Brad Gibson |

Yogic breath practices have evolved over thousands of years as yogis experimented on themselves and passed on their discoveries their students. And while some schools of yoga teach yogic breath practices (pranayama) to beginners, the type of yoga that I’m trained in, Iyengar style, considers breath practices to be so powerful that pranayama is introduced very gradually.

We’ll be introducing some simple breath practices in the coming weeks, but until then start by tuning into your breath throughout the day. When you’re standing in a long line at the post office, fighting the crowds at the grocery store, or are stuck in traffic, are you taking quick breaths, deep breaths or sighing? When you’re taking a hot bubble bath, petting your dog, or chatting with your partner after a good dinner, are you taking slow breaths, shallow breaths, or—oops!—yawning?

Tuesday, December 6, 2011

A Pair of Serendipities Re: Spinal Stenosis